Afghanistan’s opium trade is worth £14 billion a year. But when its dealers are shot or jailed, their daughters are sold as wives to settle their debts

By Fariba Nawa

May 9, 2004

Sunday Times Magazine (UK)

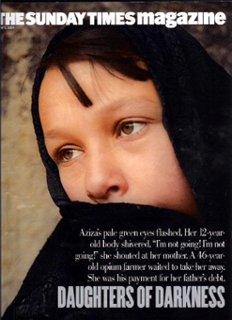

Aziza’s pale-green eyes flashed. Her 12-year-old body shivered. She took two steps back towards the mud wall in the hallway. It was a dead end. “I’m not going! I’m not going!” she shouted at her mother. Meanwhile, Haji Sufi, a 46-year-old opium farmer, waited for her, cross-legged on a thin mat, drinking black tea. He had travelled hundreds of kilometres from southern Afghanistan to collect Aziza, his wife of two years. She was his payment for taking on her father’s £2,656 opium debt. But every time he came, Aziza cursed him and ran off.

Aziza’s mother, Khadija, scowled at her daughter. “It’s your wretched father’s fault that has put us in this hell,” she said. “What’s done is done.”

Since the Taliban fell in 2001, Afghanistan’s once-regulated opium trade has been up for grabs by anyone with weapons and land. The United Nations estimates that 500,000 people are involved in the trafficking chain, and the overall turnover of illicit international trade in Afghan opiates is worth £14 billion a year. The globe’s largest opium producer, Afghanistan feeds two-thirds of the world’s demand for narcotics.

The trade is a formidable barrier to western efforts to reconstruct the country. About half its GDP comes from it, hindering efforts to build a legal economy. Western officials also fear it is helping to fund terrorism. But the war against drugs is as shadowy as the war against terrorism, with no defined enemy or borders or end in sight. The British have poured millions of pounds into trying to stop the trade, with little success. Many of those who benefit the most are the same people who now run Afghanistan’s provinces, with western support.

Opium production shot up from 185 tonnes in 2001 to 3,600 tonnes in 2003; 28 of the 32 provinces now harvest poppies. About half the opium leaves through the western border to Iran, on to Turkey and the Gulf, where it is refined into heroin and sent to Europe and beyond. Donor countries are sceptical about aiding a narcotics-producing state, but they rarely take into account the tragedies at the source of the problem.

Aziza’s home is in one of hundreds of villages forming links in the chain. Ghorian district is in Herat province, two hours from the Iranian border. Many of its 180,000 residents are drug addicts, dealers or widows. Drug lords rule, aided by a weak and corrupt local government. Husbands and sons carry opium by foot and donkey over the mountains, where they come under fire from Iranian border guards. Many never return, having been either killed in ambushes or executed in Iranian prisons. They leave behind thousands of pounds of opium debts, which are inherited by the trade’s greatest victims: women and children.

Aziza Khoshsaraj is the neighbourhood’s fair-skinned, 5ft-tall imp. To the dismay of her mother, she often plays barefoot in the creek. She is ecstatic that she can go to school after six years at home during Taliban rule. But the carefree girl becomes a raging, terrified child when Sufi arrives, bearing gifts. Her mother, Khadija, is so poor she tries to convince her to go. She wants the entire family to become Sufi’s servants, to ensure their livelihood.

Once, it was all very different. Khadija, 30, and her daughters say little about their old home, a 10-room house with a rose garden, or the kilos of gold jewellery that once hung from their necks and ears. But everybody else in Ghorian remembers. “Few here had that kind of wealth,” said Safia Hussein, a woman from the same tribe.

Aziza’s father, Maroof Khoshsaraj, 35, was an opium recruiter, the intermediary between the couriers and kingpins. He made his small fortune buying opium and sending young men to their deaths. In five years, he built a two-storey home. He also took a second wife, Shamira, a young city girl; on their wedding day, Maroof decorated almost every Land Cruiser in town with flowers.

But opium wealth is fleeting. Iran has tightened its border, partly because of its rising population of opium addicts. Few Afghan couriers return, and the opium just disappears with them. Maroof owed about £5,800. The drug barons held a gun to his head and threw him in jail several times, demanding their money. He didn’t have it, so he offered them his two daughters, Aziza and Rahima, 14. Their fair skin and curvaceous figures made the girls worth thousands of pounds. Two years ago, Maroof went into hiding, leaving his first wife, Khadija, pregnant with her sixth child. Then came the drug barons. They gave the family a few hours to pack, and then they took the house and everything that was left in it. Maroof’s second wife returned to the city with her two children to live with her parents. He has also been seen in the markets there, skinning sheep.

Khadija and her children, aged between one and 14, became homeless. Now she lives in a two-room shack belonging to a cousin in Iran. There’s a charred kitchen and an outside toilet. Khadija serves others now, making 12p to 20p a day baking bread or washing clothes. The family barely has enough to eat. They have two outfits each, a pair of shoes, a few headscarves. Her eldest daughter’s husband has not shown up, but Khadija is too afraid to wed her to another man in case he does.

Khadija is gaunt and listless. When she is not working she sits motionless, smoking her water pipe; nearly all her teeth are gone. She speaks with fatalistic absolutism: life and God have cursed her. “I live hour by hour, wondering where the next meal is coming from, when are the smugglers going to take my daughters, is my husband ever going to come home. We have peace now, but what good is it when my family may go hungry tomorrow?” she asked, nursing her youngest.

Some here believe that Herat city, an oasis in the province also called Herat, will one day be destroyed by the fierce wind that cools it during summers when the temperature reaches 40 degrees. Genghis Khan razed Herat province in the 13th century, but it re-emerged 200 years later as central Asia’s cradle of art and culture. Today it is Afghanistan’s wealthiest region, thanks to customs revenues from imports. But Ghorian is on the edge of destruction. Thirty years ago, before the communists seized control, it was a bastion of tea and fabric smuggling, but only a small amount of opium was traded. Residents lived on agriculture. During the 1979-1992 war against the Soviet-backed regime, many of Ghorian’s men joined the resistance and hundreds of families fled to Iran.

Farmers in the south and east of Afghanistan turned from wheat to poppies to help fund the resistance. Ghorian’s nomads, with their tradition of smuggling, handled the opium-trafficking to Iran. After the communists fell, the refugees returned and the only jobs were in the drug trade. What was once a business for a few select families became a source of income for half the district.

Demand rose. Iran, with more than a million addicts, became a big consumer of Afghan opium, as did Europe. In 1995 the Taliban seized Herat and encouraged the trade, collecting taxes from opium farmers and smugglers. Then a long drought killed animals and the shepherds’ livelihood. Many in the area had no skills or literacy, so even shopkeepers began selling opium. At first nobody in Ghorian knew how to grow poppies, then the Taliban brought their opium farmers from the south to show how it was done.

Jalal, 19, learnt from the Taliban how to turn his wheat and watermelon fields into poppy flowers. His family’s half-acre yielded 20 kilos of raw opium last year, the first time he’d cultivated it. “My father asked me if I wanted a wife and a car,” said Jalal. “I said I want two cars. I now transport passengers for $20 return from Ghorian to Herat city. I had nothing, not even a bicycle last year. Now I feel rich and I have a job.”

On the way to his best friend’s house, Jalal stopped to greet some men. One offered him eight kilos of opium for his car. Jalal eyed the station wagon’s steering wheel like a toddler with a new toy. “I just got this and I can’t give it up for less than 10 kilos. Let’s talk later,” he said, accelerating.

Jalal’s best friend is Tarek, a chubby, moustached 23-year-old who manages dozens of acres of land belonging to families living abroad. This year he planted opium on that land and now has enough money for his wedding. He bought a shiny Honda motorcycle and painted his mud-brick house white. Over green tea, Tarek brought out his fresh batch of black opium, a bitter, gooey liquid. “If you sell, you don’t use it. We have people who test to see if it’s pure. They’re addicts,” he said.

Unless desperate, they won’t do the border run themselves. “We deal here and hire the shepherds as our fall guys. This is the only way to stay alive and get rich,” Jalal said with a smug smile.

They like the new government. The district administration sends a six-member commission to view the cultivated land in the autumn, said Jalal, and it asks for a kilo per acre. In exchange, crops are not destroyed. The trade-off is blatant. While I was there, Jalal sat in the Ghorian police station with the assistant intelligence director. “I’m upset with your father,” the official said. “He didn’t give me my share. I expect my share.”

The conversation halted when Mohammad Sobhan, the district intelligence chief, arrived. He offered to show videos of the government destroying opium crops. “When families don’t want to give a cut, the government eliminates their crop,” Jalal explained later. Sobhan, who has since resigned, admitted the administration was soft on drug lords for political reasons but denied collaboration with farmers and smugglers. He said smugglers escaped to Zir Koh, a nearby district under a different ruler, where criminals cannot be prosecuted. But he agreed officials don’t have the manpower and weapons to fight traffickers.

It’s clear that neither government officials nor the police are trusted. The police chief had just weeded out a handful of hashish plants from a local farm and was burning them in public as an example. The watching crowd’s mood was cynical. “They probably kept most of it hidden in the fort to sell later,” a bystander whispered.

The Taliban banned opium production in 2000. Prices ÿhad dropped too low and they wanted to get rid of their stockpiles. All that changed when the American-led coalition triumphed: farmers took advantage of the power vacuum. President Hamid Karzai made the drug business illegal in January 2002, but the American-backed leader’s authority does not reach far beyond the capital, Kabul.

In Herat, the warlord Ismail Khan is the self-proclaimed emir, with an army of 20,000 soldiers backed by Iran. President Karzai has tried several times to lure him to Kabul, without success. Khan had prohibited the central Afghan anti-narcotics office from opening a branch in his fiefdom, saying there is already a bureau operating under his control. But recently, the two agencies merged and Khan is working with the central government on eradicating drugs. Publicly, he condemns the drug trade and supports a treatment clinic for the region’s booming number of addicts. If he is reaping the benefits of opium-trafficking, the evidence is hard to find. Still, suspicions about him remain. Though tight security means Herat is Afghanistan’s most peaceful province, trafficking continues. Khan, a Tajik, is said to dislike Ghorian, which is mostly Pashtun and has a reputation for revolt. He appointed a district mayor and police chief from outside to strengthen Tajik power and, two years ago, he had a Pashtun smuggler shot and killed. But even Ismail Khan can’t control the area.

“We don’t get any government help here — we’re the armpit of the province. We’re considered the smugglers and thieves,” said Dr Gol Ahmed Daanish, head of the local hospital. “Smuggling is the only income that has been encouraged.” Daanish, elegant in his western slacks and shirt, represents the small minority of educated residents who are fighting to change the district’s reputation. “It was run by a few locals who are now dead or addicted,” he said. “Now there are invisible drug mafias and bandits who control the trade, and people here have become the pawns.”

The most feared drug lords here are two cousins, Ruhollah and Kader. Their twin two-storey houses, with well-kept gardens and locked brass gates, tower over rows of dilapidated mud homes. They hail from a smaller village, Haft Chah, which breeds drug dealers with important Iranian connections, say townspeople. Ruhollah and Kader are illiterate hajis — they made the obligatory trip to Mecca three years ago. Ghorian residents respect them for that title and their rise to affluence. They were shepherds, then refugees working on construction jobs in Iran; now they’re the closest thing to mafia. Their cronies terrorise women and families with opium debts.

Yet even they have lost people close to them to drugs. Ruhollah, 35, supports the families of two siblings, since their men died smuggling narcotics. He agreed to an interview on the condition that he would not talk about his smuggling activities. Inside his spotless seven-bedroom house, the whispers of his wives and extended family echoed from behind closed doors. Ruhollah sat on a gleaming Persian carpet next to his adopted daughter, Soghra, 10, who was sporting sunglasses.

“This route has belonged to smugglers through Afghanistan’s history,” he said. “It’s not a crime. People do it because they are hungry.” He claimed his family made their money from sheep-herding and money exchanges; locals claim it’s a front for their drug business. He said his fortune was worth only £12,000. He was friends with the Taliban and is now friends with the new, coalition-backed government. “My family has been able to adapt to government changes.” He is said to have taken over from the original opium-trafficking clan, the Soltanzi. They knew the mountain and desert passes of the old Silk Road blindfolded, and nobody dared stop them. But as Iran toughened its stance, the clan lost its authority and income. Its women are now under Ruhollah’s power.

In Shau Bibi Soltanzi’s three-room mud house, the light shines on a photograph of her husband, Shahpoor, and her son Qader, both executed in an Iranian prison 11 years ago. Her eldest son, Kader, died in battle against the Soviets. Her son Nader was captured by the Iranians and has left her with a huge opium debt. Her other son, Wahid, is a drug addict in Iran. She has not put up pictures of her daughters because it’s not proper to display women’s photos. But she has a photograph of her youngest daughter, Bibi Shah, in a clear plastic bag. The 17-year-old died three years ago in her mother’s home. She had poured cooking gas on herself and lit a match. She died two months later, moaning in agony from her injuries.

Bibi Shah’s husband was killed carting opium. Her two brothers-in-law both offered to marry her, according to tradition, but she refused. Her in-laws accused her of wanting to remarry for a dowry, and her mother says they beat her until they tore her eardrum. They locked her up in the house and would not let her family see her. She kept a knife under her pillow when she slept, afraid that her brothers-in-law would rape her. One day, Bibi Shah lost hope completely.

Her mother — left only with her other daughter, Gulaby, also a widow with two small sons — is losing her mind. She is often not able to articulate a coherent thought. She and Gulaby borrow the equivalent of 60p to buy four kilos of wool, spinning it into yarn for carpets. It takes 10 days and they sell the yarn for £1. They spend 15p a day, including their diet of onions, bread and dried curds. Shau Bibi, in her chador and her tattered shoes, searches for thorn and hay in the desert, which she sells to shepherds as fodder and fuel for a few pence. And now she has started growing opium in her yard in order to survive. Her family had long transported the drug.

“We didn’t make much money in the old days. For a kilo the men took across the border, they got a sack of flour. Now the stakes are higher and so is the cost to your life.” Her son Nader, 24, was well known as a ruthless dealer. Shau Bibi wanted him to stop and convinced him to get engaged. The bride’s family demanded a £2,300 dowry. Nader made the dangerous trip himself to earn it and pay his debts. It was three years before Shau Bibi received news that Iranians had caught him alive — with three dead cohorts. Now she owed southern Afghan dealers and Ruhollah £4,600. “They were Taliban; they came and took the carpets, motorcycle, prayer rugs and the land. Haji Ruhollah left me with nothing,” she wept. Khan, Herat’s governor, has said that all opium debts are forgiven, but Shau Bibi’s creditors keep coming. Some are police, she said. On Friday, the Islamic holy day, she goes to the cemetery and grieves at the unmarked graves of Bibi Shah and Kader.

Shau Bibi said she knew why the government didn’t act against Ruhollah and his cousin Kader. “Everyone knows these two terrorise and control Ghorian. Why don’t they put them in jail? Because they can’t. They have more money and power than Ismail Khan and Karzai. Or else the government cannot survive without them and their money.”

The US defence secretary, Donald Rumsfeld, said in September that he did not know how the United States would tackle Afghanistan becoming a drug state that funded coalition opponents. Britain’s 10-year counter-narcotics strategy includes law enforcement, alternative crop options and reduction of demand. But critics say both countries, by commending warlords who engage in the trade but who also support the coalition, weaken international efforts to stamp it out. In early 2002, Britain compensated farmers by £200 an acre for eliminating opium crops. Boxes of cash — £21.25m in all — were flown into the east and south, and distributed to local authorities. About 4,500 acres of poppy harvest were destroyed. But, according to the Dutch-based Transnational Institute, which studies drugs in Afghanistan, many district governors pocketed the money instead, and farmers continued to plant poppies.

New anti-drug laws have been passed and Mirwais Yasini, director of the anti-narcotics office, claims a reduction in the southern poppy belt as a result. President Karzai’s recent reshuffling of ministers and governors is also an effort to root out drug traders. But halting trafficking is the hardest challenge because its dynamics and criminal networks are unknown to authorities, said Adam Bouloukos of the UN Office of Drugs and Crime. Increasingly, smugglers are avoiding Iran and passing through Tajikistan instead because of its lax security.

Iran has lost at least 3,000 troops in its fight against trafficking in the past decade. It has added another 25 specialist border patrols to the 100,000 troops already along the 925-kilometre frontier. Traffickers say the troops shoot to kill. On the Afghan side at one checkpoint, three sleepy-eyed guards emerged from a bombed-out barrack. Each carried a rifle, but said they had no communication devices, no vehicle, not even binoculars. In two years, they have only caught five men, carrying just 10 kilos. However, they denied collusion, claiming the route was watched too carefully by Iranians for traffickers to pass.

Two hundred yards away was the Iranian border post, with armed guards on all four sides, scouting the vast desert through binoculars. Beyond a large, bullet-pocked black stone, the border marker, is Iran and its paved roads and electricity poles. The Iranians are on orders to shoot anything moving past the foot-long rock, and there was a row recently when they shot sheep at night. “We told them the sheep don’t understand borders,” said Khan Mohammed, an Afghan soldier. “They say they have to follow orders.”

A retired smuggler, Nasim Siah, 32, knows how dangerous his old profession is. Of 21 of his trafficking allies, he is the only one who is free and alive. He began smuggling when he wanted to marry for a second time. The girl’s father asked for a £7,000 dowry, and drugs were the fastest way to get it. He borrowed 1,500 kilos of opium and took it to Iran. Twice, other traffickers shot at his crew. They reached the mountain where the opium was to be unloaded. After 30 days, their Iranian contact appeared. Iranian shepherds are go-betweens for Afghan vendors and Iranian buyers; they also serve as Iranian informers. Siah considers himself lucky. He made it back to present the £7,000 to his bride’s father. “I know more than a dozen girls sold to farmers in the south for opium debts and more than a thousand women who have been widowed.” Ghorian residents say the Siah brothers quit trafficking opium because they were losing money; now they rob jewellery stores and moneychangers.

Anti-drugs campaigners are trying to encourage women to stop their men becoming involved. One day the district mayor gave a fiery speech to 3,000 women gathered at the girls’ high school in Ghorian, and two girls performed a skit about a mother who convinces her son to give up smuggling and addiction. Some of the women cried as they watched, tears of anguish and hope.

For Aziza, the bartered child bride, hope may be dim. Sufi says he does not want to force her but she will eventually have to go with him. “Here, girls do not have the right to decide who they marry. Her father promised her to me. I will be patient, but I am her husband… My wife is ill and needs help in the house. I expect this girl to help her but she is rebellious. We hope she will change.”

The Herat government has banned bartering girls for opium debts, but the couple are already married under Islamic law, making an annulment nearly impossible under tribal values.

After leaving Ghorian, I heard that Aziza came looking for me. She had walked an hour against the wind. “He’s left, but he swore to come back and take me,” she told my hosts. “Please tell her to make him leave me alone.” But I was long gone.

Written by :

Subscribe To My Newsletter

BE NOTIFIED ABOUT BOOK SIGNING TOUR DATES

Donec fringilla nunc eu turpis dignissim, at euismod sapien tincidunt.

Related Posts

Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh aulvinar. Praesent sapien massa, convallis a pellentesque nec egestas.

More Details

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Donec velit neque, auctor sit amet aliquam vel, ullamcorper sit amet ligula. Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat. Vivamus suscipit tortor eget felis porttitor volutpat. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec rutrum congue leo eget malesuada. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt.

Vestibulum Ante Ipsum Primis In

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Donec velit neque, auctor sit amet aliquam vel, ullamcorper sit amet ligula. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Donec rutrum congue leo eget malesuada. Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat.Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh aulvinar. Praesent sapien massa, convallis a pellentesque nec egestas.

More Details

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Donec velit neque, auctor sit amet aliquam vel, ullamcorper sit amet ligula. Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat. Vivamus suscipit tortor eget felis porttitor volutpat. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec rutrum congue leo eget malesuada. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt.

Vestibulum Ante Ipsum Primis In

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Donec velit neque, auctor sit amet aliquam vel, ullamcorper sit amet ligula. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Donec rutrum congue leo eget malesuada. Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat.Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh aulvinar. Praesent sapien massa, convallis a pellentesque nec egestas.

More Details

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Donec velit neque, auctor sit amet aliquam vel, ullamcorper sit amet ligula. Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat. Vivamus suscipit tortor eget felis porttitor volutpat. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Donec rutrum congue leo eget malesuada. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt.

Vestibulum Ante Ipsum Primis In

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Donec velit neque, auctor sit amet aliquam vel, ullamcorper sit amet ligula. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Donec rutrum congue leo eget malesuada. Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat.Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.

Vivamus magna justo, lacinia eget consectetur sed, convallis at tellus. Mauris blandit aliquet elit, eget tincidunt nibh pulvinar a. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.